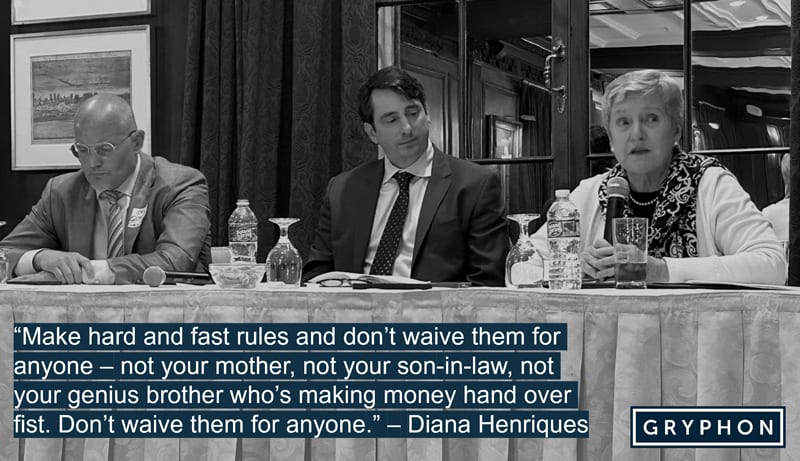

Last week, Gryphon Strategies and Shadmoor Advisors invited Diana B. Henriques, award-winning financial journalist and New York Times bestselling author of “The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust,” to participate in a panel discussion titled, “Too Good to Be True: What Madoff’s Fall Taught Us About the Power of Due Diligence.” The discussion and networking event was hosted at the Harvard Club of New York City. Other panel participants included Jay Dawdy, president & CEO of Gryphon Strategies, and David Umbricht, Managing Director of Shadmoor Advisors.

As a staff writer for The New York Times from 1989 to 2012, and as a contributing writer since then, Henriques has largely specialized in investigative reporting on white-collar crime, market regulation and corporate governance. Henriques’ book details Bernie Madoff’s scheme, one of the largest scandals in financial history, estimated to have cost investors approximately $17.5 billion in losses.

“How do you defend in due diligence work against that guy or against that gal?” Henriques asked. “How do you detect a Ponzi scheme?” she continued. “You locate the assets and you confirm that they’re there. It’s like checking the inventory if you’re a CPA conducting an audit, you need proof that it’s there. Madoff’s biggest red flag: He didn’t use an independent third-party custodian to hold the assets – although he was operating on a multi-billion dollar scale. Red flag the size of the Empire State building.”

Henriques said she has been struck by the parallels between some of the scandals that have broken recently, particularly in the crypto market, referring to Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX. Bankman-Fried looked nothing like Bernie, she said, but he was using Bernie’s rules: “Bernie wore Saville Row suits and handcrafted shoes because the people he was trying to attract wore or admired people who wore Saville Row suits. Sam Bankman-Fried wore cargo pants and hoodies because that was what the genius of Silicon Valley was supposed to wear, so it was protective coloration although they were dramatically different.”

Regarding these commonalities, Dawdy said, “Part of having a very core group of related individuals in power positions who are able to ignore the outside world and ignore the rules are common things you see throughout those three cases.”

Another commonality between FTX and Madoff was having a close-knit group of relatives and friends that helped facilitate their frauds, Dawdy continued. “In the FTX case, it was his girlfriend; in Madoff’s case, it was his brother. For a due diligence person, that should’ve raised a red flag.”

“Family ties make due diligence difficult,” Henriques responded. “You won’t see the danger, you won’t see the red flags, and they will know that you won’t see the red flags, and the temptations will be even more severe if they’re under pressure that you’re not aware of, so just don’t do business with family.”

So what does an investor do when a) they’re genetically inclined to trust people and b) someone like Madoff is an inherently trustworthy person? Henriques related a story about an investor who had heard of Madoff’s successful returns and finally, after being denied time and again, got an appointment with him. Madoff insisted the buy-in was $5 million, but the investor said he would only start with $250,000. He and Madoff went back and forth but, in the end, the investor didn’t budge and walked out the door – likely saving himself millions of dollars. “The man had an inflexible, hard and fast rule that made sense to him, served him well and was tempted to waive it for this genius, this wizard of Wall Street,” said Henriques. “Make hard and fast rules and don’t waive them for anyone – not your mother, not your son-in-law, not your genius brother who’s making money hand over fist. Don’t waive them for anyone.”

An audience member asked the panel if they thought the Draconian prison sentences would be a deterrent to future con artists.

“It’s often not the severity of the punishment, but it’s the perception of detection,” said Dawdy. “So how likely are they to be caught, or how likely do they think they are to be caught, and if they don’t feel like there’s much likelihood, regardless of how severe the penalty is, they’re going to go ahead and commit that fraud.”

“Years after Madoff, people still want to hear about this,” Umbricht said. As a way to explain how Madoff was able to pull off such a grand scheme, Henriques said, “As a species, we’re hardwired to trust each other. It made sense to trust Bernie Madoff. To be a successful con artist you must be able to inspire and keep that kind of trust in the face of hell or high water – and Bernie could. He was the kind of person who doesn’t have to hack your computer because you trust them so much that you give them the password.” Henriques felt that the besetting sin of these con artists was not greed, but it was pride. “Madoff could live with himself as a liar,” she said, “but he couldn’t live with himself as a failure.”